Pelican 16 Down:

The story of a grand old lady lost in the Sahara desert

Part 3 of the Shackleton MR3 in SAAF Service

SAAF Shackleton 1716, call-sign "Pelican 16" was the first Avro Shackleton built for the South African Air Force and the first to go into service upon its delivery on August 18th, 1957. Eventually joined by seven other aircraft, Pelican 16 formed part of the SAAF's 35 Squadron and for the next 27 years served as part of South Africa's Air Force patrolling the sea lanes around the Cape of Good Hope.

Side-lined by a combination of air frame fatigue and lack of spares due to apartheid-era embargoes on South Africa, Pelican 16 and the balance of the SAAF's Shackleton fleet were placed into storage by 1990.

Restored to flying condition by volunteers in 1994, Pelican 16 was offered to take part in a multi-stop air show tour in the UK and departed South Africa for England on July 12th, 1994, taking in the famous Farnborough Airshow. At the time she was the only airworthy Shackleton MR3 in the world.

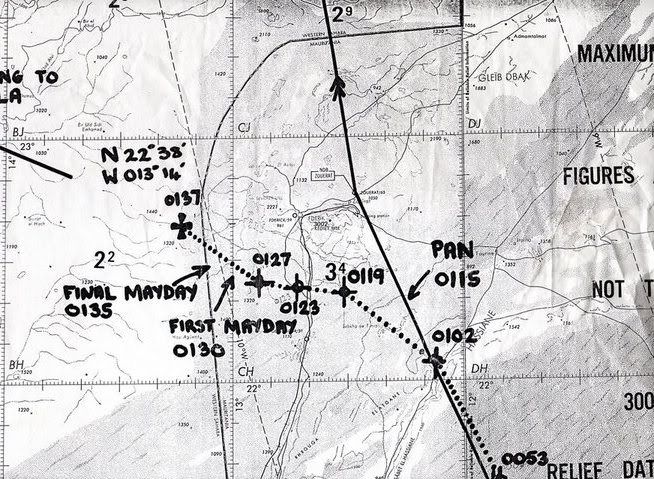

Flown by a group of active SAAF pilots, Pelican 16 was operating over the Sahara desert in temperatures exceeding 38 deg C/100 deg F on the night of July 13th when her number 4 engine began to overheat from a coolant leak and had to be shut down. Moments later, a bolt connecting her two contra-rotating propellers in her no 3 engine failed, causing the assembly to overheat and melt and leaving the fuel-laden plane without any functional engines on its right wing.

Left no option but a controlled ditching in the desert below, Pelican 16's pilots successfully belly-landed their aircraft on flat sands where it slid to a stop at this location. Though none of the crew were injured by the landing, all 19 men were miles from any assistance and in the middle of an active war zone. Through the next several days, the crew of Pelican 16 made their way to the safety of friendly forces and returned safely to South Africa.

The rescue

Today, the wreckage of Pelican 16 still remains where she came to a stop on the night of June 13th, 1994.

On the morning of 13 July 1994 the headline news in The Argus newspaper read “SAAF Plane Down in Desert”. Today, twelve years later and although she was found, Pelican 16 is for the records still “missing-in-action”; and remains at the crash site (click for panoramio map)

Enough has been written in the past on Pelican 16 and her last resting place in the Western Sahara when she hugged the sand with her belly on the night of 13 July 1994 after an emergency landing when her number 3 and 4 engines on her starboard side ignited and burned. A documentary by Andrew White told the story in great detail. The radio transmission that was made with military precision and efficiency are told to be used even today by the SA Air Force in their training as a text book example of how it should be done.

One can only begin to understand the legacy of, and the passion for this remarkable aircraft once you have heard for yourself the mighty roar of the four Rolls Royce Griffon engines. Everything else is only then put into perspective if you are lucky enough to touch the fuselage and ride the winds on the mighty wings of this Avro Shackleton MK3 called the “Pelican”.

This aircraft to some is bigger than religion and greater than fantasy… Today a few survivors from the crash still believe that she should have been brought home years ago and others are of the opinion that it is significant to let her rest where she came to a halt. Be as it may South Africa is still very fortunate to have Pelican 22 still flying at Air Force Base Ysterplaat in Cape Town and to hear the four fabulous Griffons growl!

The crew who had to leave Pelican 16 behind:

Eric Pienaar (Pilot)

Peter Dagg (Co-Pilot)

John Balledon (2nd Co-Pilot)

Derick Page (Public Relations Coordinator)

Blake Vorster (Navigation Leader)

Horace Blok (2nd Navigator)

Frans Fourie (Flight Engineer)

Buks Bronkhorst (Aircraft Fitter)

JP van Zyl (Flight Engineer)

James Potgieter (Aircraft Fitter)

Lionel Ashbury (Telecom Operator)

Freddy Deutshmann (Radio Operator)

Chris Viviers (Radio Operator)

Pine Pienaar (Aircraft Electrician)

Spud Murphy (Radio Technician)

Ron Bussio (Museum Curator)

Gus Gusse (Aircraft Fitter)

Bobby Whitfield-Jones (Instrument Fitter)

Tony Adonis (Treasurer)

Lost in the desert sands: A first-hand account:

The South Africans Air Force crew who crash-landed this plane in the Sahara Desert were rescued with the help of a message dropped from the sky and a rebel movement.

This is all that's left of the SA Air Force Shackleton 1716, forever abandoned in the sand.

"No way will you ever hear that sound again," said mission commander Hartog "Horace" Blok.

He was reminiscing over the long-gone sound of the Shackleton's four Rolls Royce Griffon engines.

"The sound those engines make is just so unique. It's a sound that nothing can emulate, it's a beautiful sound."

Blok is now involved in aviation in the private sector.

These photographs were taken by United Nations officials who passed by the wreck recently.

In July 1994 the Shackleton, known as Pelican 16, had been refurbished in a huge project, and the team was flying from SA to England to take part in a series of airshows.

At the time The Star reported the aircraft was one of only two airworthy Shackletons left in the world, and had about 1 000 hours of airframe time left before being permanently grounded.

It had been used for maritime patrols off the South African coast until a few years before its last trip.

But en route to the English airshows, at night over the Sahara, the Shackleton had engine trouble and pilot Eric Pienaar had to crash land at 1.40am.

"It was pitch black. There was no horizon," remembered Blok.

"We just flew until we hit something.

"It's an anxiety attack that I never ever want to relive."

Driven by terror of fire, they fled from the plane and scattered.

Blok blew a whistle to get everyone together and, joining hands, they counted all 19 occupants.

Only two were slightly injured.

Still holding hands to stay together, one survivor led them in the Lord's Prayer - a ritual re-enacted at the survivors' union every year.

They had sent mayday messages shortly before crashing, but after that lost radio contact.

On the ground they set off a satellite-linked signal beacon - initially ignored by rescuers who disbelieved a signal from the Sahara.

At sunrise, they attracted the attention of a French naval plane from Morocco by burning a tyre.

The French plane couldn't land, but eventually got help - by writing a note, shoving it into a plastic Coke bottle and dropping it on a UN team in two vehicles in the desert.

"One aircraft has crashed near your position - 19 persons on board.

"Position 015/10km from you. We try to contact you on frequency 1215 or 243 MHZ. GPS position 2238 north 01314 west," read the note.

Blok said the UN team fortunately included someone who spoke English, so could read the note.

Horrified at the prospect of 19 people mangled in an air crash, the UN team rushed to the scene.

"And there were the South Africans, beers in hand," said Blok.

The crash site was near Agwanit in the Western Sahara, for years in dispute between Morocco and the Polisaro Front, a Sahrawi rebel movement working for independence for the region.

The Shackleton survivors were helped by the Polisaro, even though South Africa did not recognise its government-in-exile until 10 years later.

The territory is still disputed.

"They took extremely good care of us," said Blok.

Within hours, the survivors had all been picked up.

"The last one of us left the crash site at 11.45am local time," Blok said.

The plane was written off as too difficult to salvage.

Now all that remains in the desert is the wreck of the grey- and-white plane, one of the last Shackletons to fly.

Is it possible to reach the wreck site from Awsard in Western Sahara ?

ReplyDelete